History

A Short History of Organ Grinders

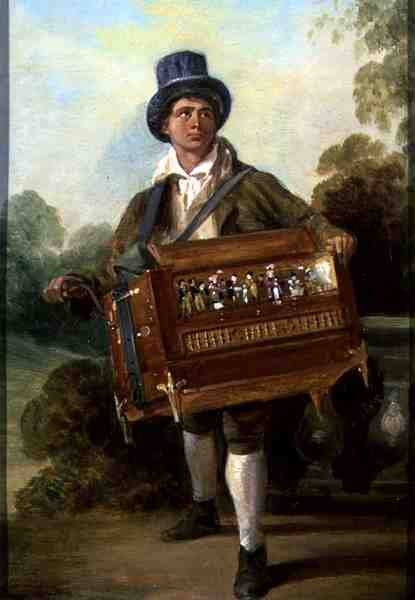

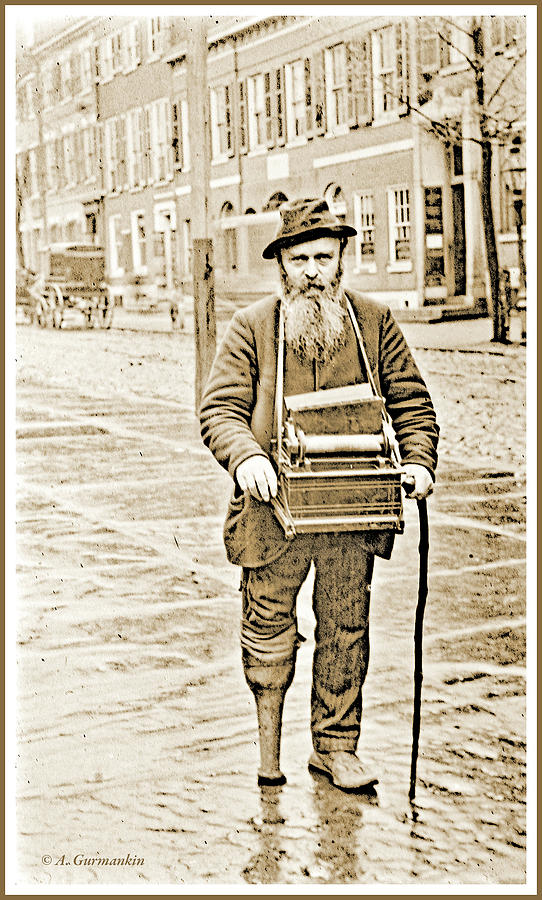

For centuries, organ grinders brought music to the streets—cranking out melodies on portable mechanical organs to entertain passersby in cities across Europe and beyond.

Origins in Europe

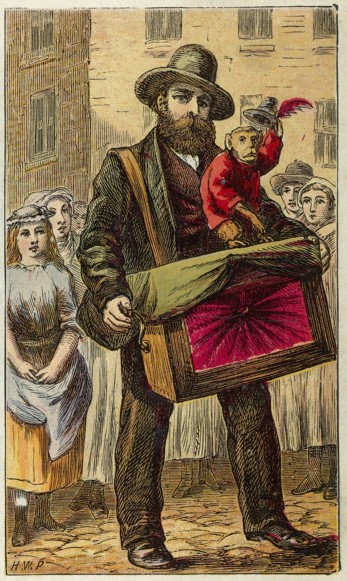

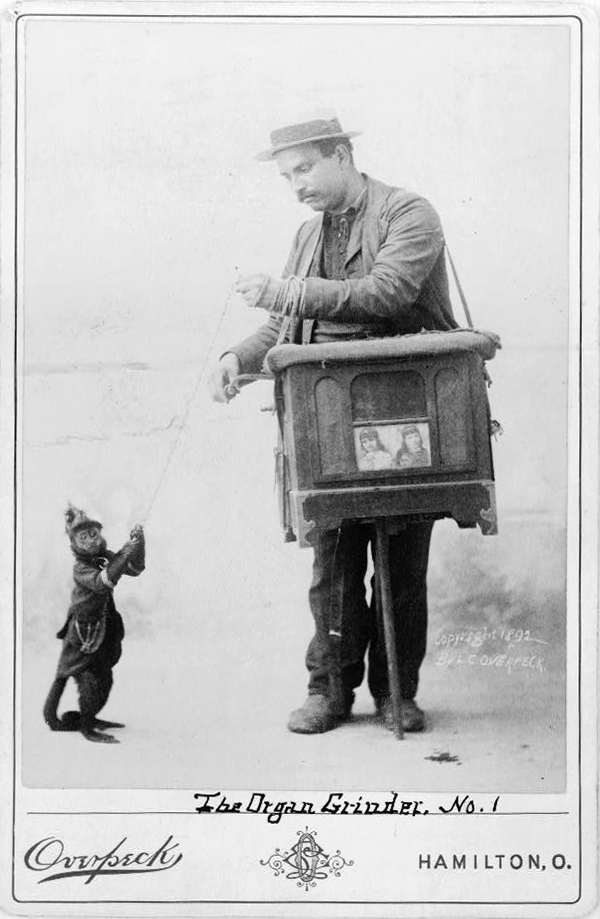

The first barrel organs appeared in the 1700s, evolving from church organs and fairground instruments. By the 1800s, smaller, portable versions allowed musicians—often poor or itinerant performers—to earn a living playing popular tunes in public squares, markets, and door-to-door. These organ grinders became part of daily life in cities like Paris, Rome, Vienna, and Berlin. Some traveled with dancing monkeys or puppets.

The Evolution of Mechanical Music: From Barrels to Paper Rolls

Early street and fairground organs were powered by pinned wooden barrels—similar in concept to a music box. As the organ grinder turned the crank, the rotating barrel triggered levers that opened valves, allowing air from bellows to flow through tuned pipes.

While ingenious, barrel organs had a major limitation: each barrel could only play a few tunes, and changing songs required physically swapping out the heavy wooden component. That changed in the 19th century with the invention of punched paper roll systems, inspired in part by the Jacquard loom—a revolutionary textile machine that used punched cards to automate weaving patterns.

By the mid-1800s, paper roll and book music systems began replacing barrels, especially in organs used for traveling shows and street performance. This evolution allowed organ grinders—and later, carousel and fairground organ operators—to carry vast repertoires of popular music wherever they went.

The Organ Grinder in America

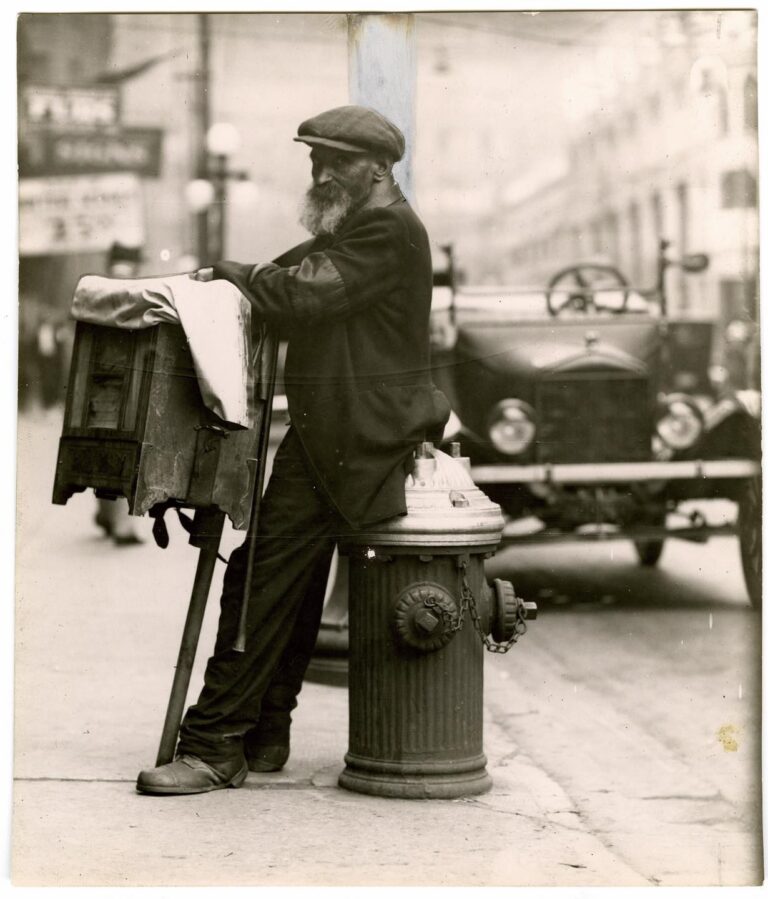

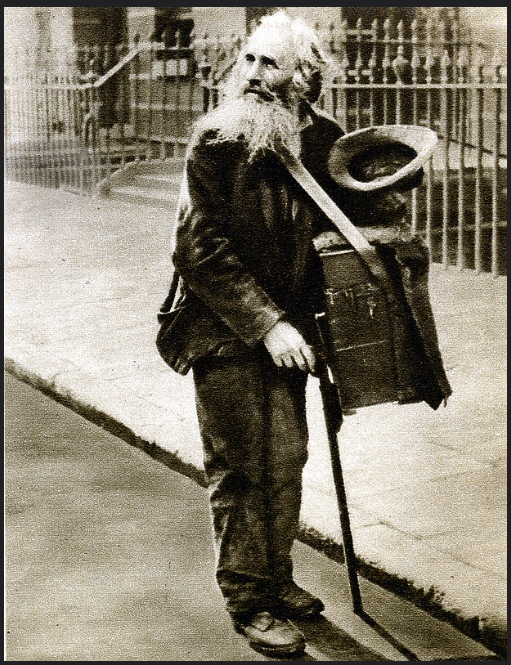

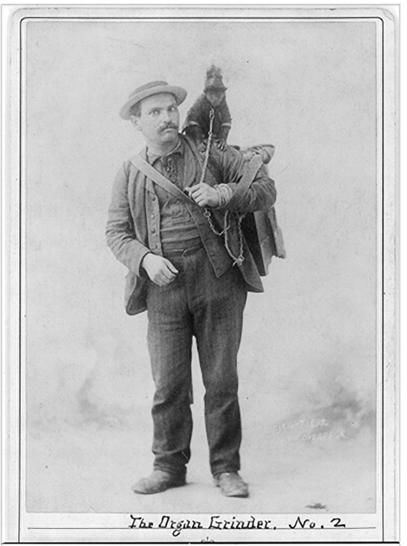

By the mid-1800s, the tradition of organ grinding had crossed the Atlantic, arriving in American port cities alongside waves of European immigrants. In New York City, organ grinders became a familiar part of the streetscape—especially in working-class and immigrant neighborhoods such as Little Italy and the Lower East Side.

Most American organ grinders were Italian immigrants, many of whom arrived with little more than a hand organ and a dream of making a living through music. Their instruments, often imported from renowned builders in Germany, France, and Italy, were both livelihood and lifeline.

As the popularity of street organs grew, organ builders and repairers emerged right in New York City. Notably, firms such as Trueman & Sons and other smaller shops operated in the city during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, servicing local performers and building new instruments for the American market. These builders often produced barrel organs tailored to the unique tastes and musical preferences of U.S. audiences.

However, by the 1930s, most of these organ workshops had shuttered. Several factors contributed to their decline:

The advent of recorded music and radio, which reduced public interest in mechanical music.

Growing complaints about street noise, especially from the rising middle class.

Increasingly strict city ordinances aimed at reducing what officials saw as nuisance street activity.

One of the most notable turning points came in 1935, when Mayor Fiorello La Guardia famously banned street organ grinding in New York. He cited concerns about traffic obstruction and the “begging monkeys” that often accompanied grinders, but there was also a cultural shift underway—one that viewed organ grinding as outdated and unsightly in a modernizing city.

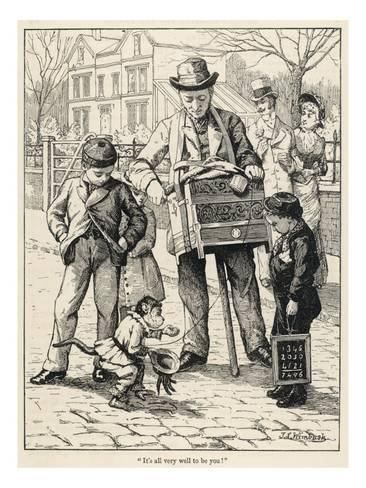

Yet despite these pressures, organ grinders remained a beloved fixture in popular culture. They appeared in newspaper illustrations, silent films, and even cartoons—often romanticized as gentle figures bringing joy to children or standing as symbols of immigrant perseverance.

To this day, the image of the organ grinder with his crank organ and capuchin monkey remains one of the most enduring icons of Old New York—a poignant reminder of a time when music echoed from the sidewalks and every street corner had a story.

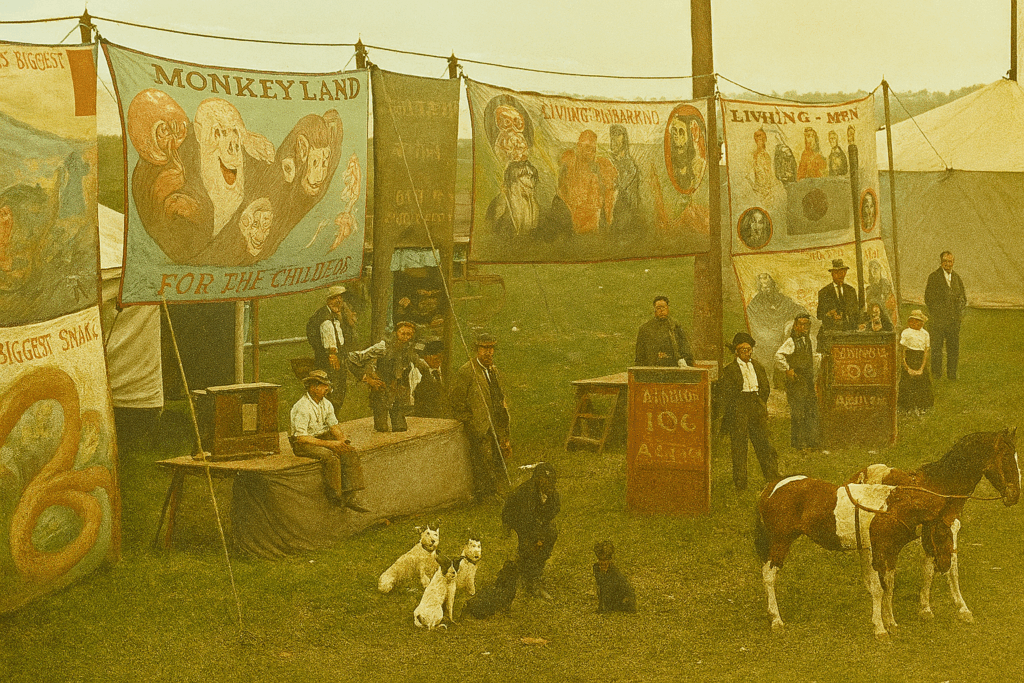

Organ Grinders and the Traveling Circus

The cheerful, mechanical music of street organs found a natural home within the world of traveling circuses, sideshows, and itinerant performances. These hand-cranked instruments were more than musical novelties—they were powerful tools of attraction. Showmen used them to announce their arrival, draw crowds to the lot, and create atmosphere long before the first acrobat took the ring.

In the days before loudspeakers and sound trucks, the street organ’s distinctive sound could be heard blocks away, signaling that something exciting was coming to town. During circus parades, a small organ might be mounted on a wagon and cranked as part of the procession, nestled between clowns, costumed performers, exotic animals, and painted banners.

On the sideshow midway, organ grinders often worked near the entrance to the “bally platform”—the elevated stage where talkers (or barkers) would deliver rapid-fire spiels to entice passersby. The music helped stir excitement, set the tone, and quite literally added rhythm to the pitch.

“The voice of the melodious hand organ was heard thro’ the land mighty early this morning. Circus Day.”

— Jackson Daily Citizen, Michigan, 1872

Some performers were multi-talented: cranking the organ, working a small marionette theater, or even managing dancing animal acts—turning a single wagon or roadside pitch into a complete miniature show. These self-contained spectacles were especially popular in rural towns, where the arrival of a circus or carnival might be the biggest event of the season.

The organ’s portability made it ideal not only for the main event but for traveling puppet shows, medicine shows, and vaudeville-inspired roadside acts. In Europe, this synergy dated back to the 18th century, with traditions like the Italian commedia dell’arte, where hand organs often accompanied street plays and shadow puppet shows.

Together, the sound of the organ, the motion of the puppets, the color of the banners, and the energy of the crowd formed a kind of “visual cacophony”—a sensory overload designed to stop foot traffic and fill the tent.